|

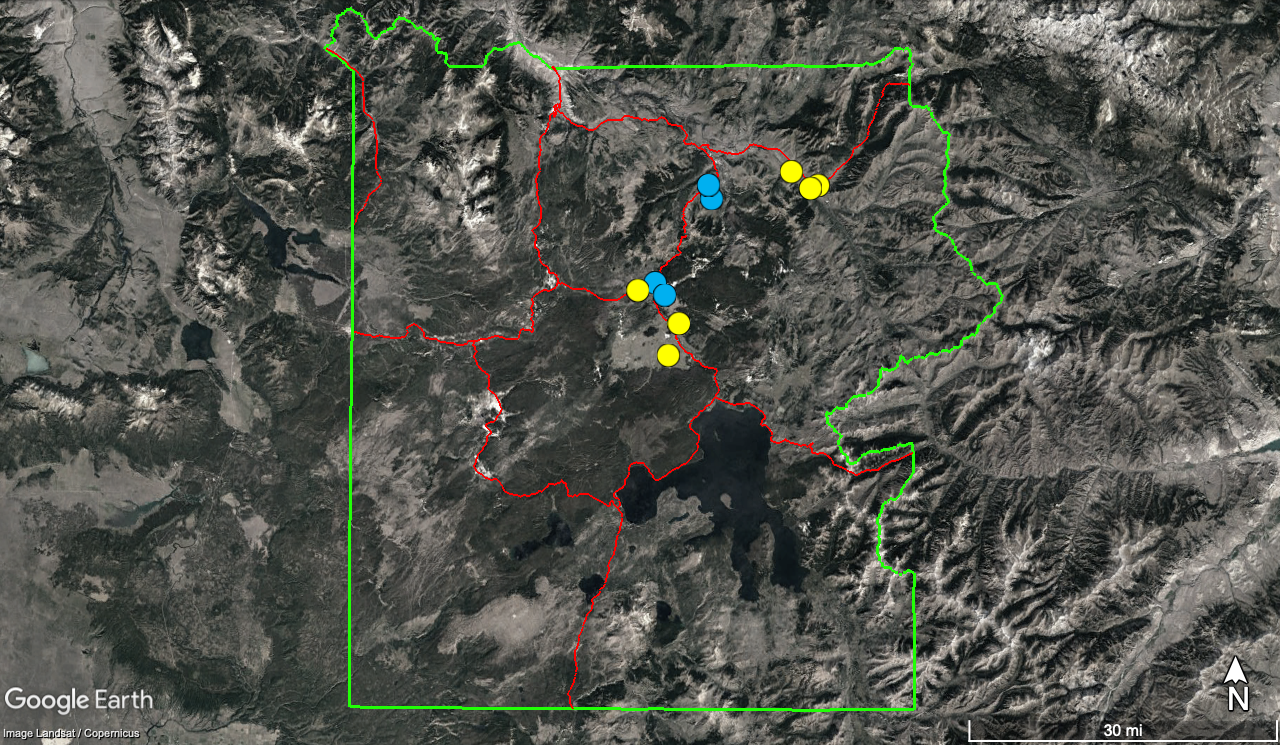

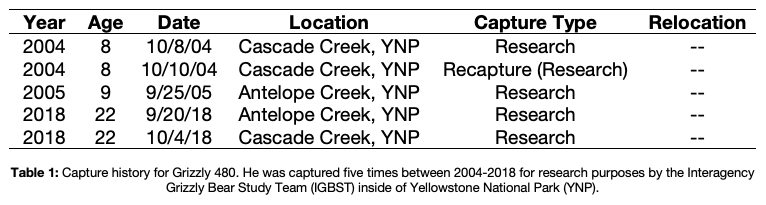

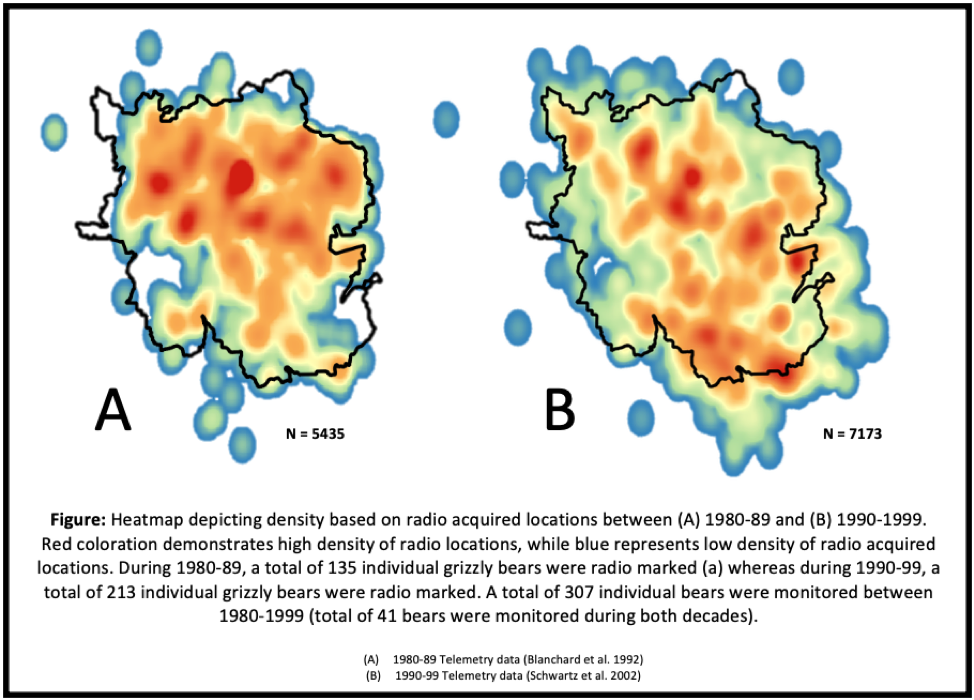

Grizzly 480 was born sometime around 1996, somewhere in the confines of Yellowstone National Park. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) first captured grizzly 480 at Cascade Creek, YNP, on October 8, 2004. His capture was part of the annual research and monitoring initiative set forth by the IGBST. During this initial capture, he was first marked and radio-collared. Two-days post initial capture grizzly 480 found himself back into the same trap; he was released on-site and not handled. Just short of one-year, on September 25, 2005, grizzly 480 was captured at Antelope Creek, YNP. The following year during 2006, grizzly 480 ‘shucked’ his collar (dropped). There was a hiatus in monitoring for grizzly 480; nearly 13-years elapsed until grizzly 480 made contact with IGBST researchers. On September 20, 2018, grizzly 480 was captured at Antelope Creek, YNP. During his handling, they collared him for research monitoring. Two weeks later, researchers captured grizzly 480 at Cascade Creek, YNP. Between his first and second captures in 2018, he cast his collar. At the time of the second subsequent capture, he was released and not handled (Haroldson et al. 2005, 2006, 2007, 2018) Grizzly 480 displays traditional movements for a male grizzly bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). Unlike females and females with cubs, males have much larger home ranges. Also, males do not display a high level of fidelity to their home ranges as females exhibit. Home range size is a function of resource availability; as sizes of home ranges decrease, habitat quality increases (Steiniger et al. 2010). A home range is defined as the “area traversed by the individual in its normal activities of food gathering, mating, and caring for young” (Burt, 1943). Home ranges are incredibly variable based on sex, age, and demographic groups. Several factors should be considered with the construction of home ranges for grizzly bears (Munro et al. 2006, Ross 2002, McLellan 1989). 1. Grizzlies are omnivorous and eat primarily vegetation. 2. Often, they will roam widely in search of berries and food sources during late summer and autumn (dispersal, and motivated by food) 3. They are not territorial (their home ranges do overlap!) 4. Adult and subadult males will have home ranges known to be several times larger than that of females 5. Home range is directly impacted by population density 6. Bears may move hundreds of kilometers during dispersal. 7. Grizzlies are known to avoid some environments such as high elevations with rocks, snow, mainly because of limited food; however, that does not exclude them crossing such an environment. 8. Grizzlies are slow to mature and reproduce (one of the slowest reproductive rates amongst all terrestrial mammals) As mentioned, population density can greatly influence grizzly movements. In areas of high density or similar necessity for nutritional resources, ranges exhibited by female grizzlies are much smaller as opposed to those home ranges documented in low-density areas. This change is likely due to competition for space, and areas of frequent foraging; also the avoidance of dominant male grizzlies (Blanchard & Knight 1991, Dahle & Swenson 2003, Schwartz et al. 2003, Dahle et al. 2006, Edwards et al. 2013, Bjornlie et al. 2014). Patterns of movement are generally food driven; early spring, when bears first emerge from their dens, they will move to lower elevations in valley regions, where there is likely absence of snow, in efforts to find new green vegetation. Females with cubs-of-the-year (COY), however, will likely remain at higher, less preferred areas close to the den, due to the need for security of their cubs during a time of lacking mobility. As spring progresses, movements increase, and this stays true until the fall for most bears. In the case of grizzly 480, an adult male grizzly bear, their movements generally peak during May & June. Daily activity and movement levels for both male and female grizzly bears typically peak during dawn or dusk, which we refer to as a “crepuscular activity pattern.” Despite significant changes in distribution, and the availability of specific food resources and habitat, lifetime home ranges did not change for male or female grizzly bears and remained consistent between 1975-1993 in comparison to 1994-2012. Works Cited

1 Comment

Rich Parkhurst

3/12/2020 07:03:36 pm

Interesting article. I’m returning for my third year at Grant Village. In 2018 had the pleasure of observing Snow late in day in September. A ranger described her as a subadult female four years old. Is it likely she will have cubs with her this year.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorTyler Brasington is a native born and raised Pennsylvanian, yet proud current Wisconsin resident. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater with a B.S. in Environmental Science. Currently, Tyler is pursuing his masters in Natural Resources with the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He has worked in Yellowstone National Park under the guidance and supervision of Dr. George Clokey and Dr. Jim Halfpenny. Disclaimer: The information and views expressed on this page do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Interior, US Geological Survey, National Park Service or the United States Government.

The Greater Yellowstone Grizzly Project

www.yellowstonegrizzlyproject.org © 2021 Tyler Brasington All rights reserved. No portion of this website may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, or appropriate authors, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. For permissions contact: [email protected] Archives

February 2021

Categories |

- Welcome

- Home

- About

- Submit sightings

- Family Tracker

- Publications & Research

- Natural Life History

- Cementum Age Determination for Grizzly Bears

- Nutrition & Diet

- Radio Telemetry and Wildlife Tracking

- Chemical Immobilization and Wildlife Handling

- Infectious Disease in Bears

- Effects of Wildfire on Grizzly Bears: Yellowstone 1988

- Mortality Database

- Photo gallery

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed