Chemical Immobilization, Capture and Handling:

In today’s day and age, you can no longer go out and purchase a dart gun and darts and learn by trial and error. Any person who may chemically immobilize, or who needs to capture wild animals needs to be trained accordingly. Capturing and chemically immobilizing a bear or any wildlife could be the most traumatic incident during its life, so it is extremely important to justify all capture and trapping events.

During chemical immobilization and capture operations, a wildlife veterinarian should be consulted and part of the team. Federal regulations require that research facilities and entities, animal dealers and exhibitors have an attending veterinarian to consult and provide guidance on capture and chemical immobilization procedures and techniques.

The handling of all captured animals should be performed in a careful manner and as expediently as possible. This is to ensure that no trauma, behavioral distress, or unnecessary discomfort can occur. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determines what drugs can be used on certain animals. The FDA also requires a registration certificate for those using controlled substances; these can be obtained through the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Personnel or field technicians who may be using or even administering controlled drugs must be working under the supervision of a certificate holder. The certificate holder is also the party responsible for keeping detailed logs, and ensuring proper storage for all drugs. Individually, some states have strict veterinary codes which should be adhered to by anyone participating or engaging in the immobilization and capture of wild animals through chemical (drug) means.

Taking part in captures using chemical immobilization is dangerous, and any individual who immobilizes or takes part in a chemical immobilization is assuming a great deal of responsibility. Each time capture operations take place, two questions should be asked:

In order for capture and immobilization to go smoothly, any individual involved needs to know his or her duty in the operation. This includes having a well-rounded understanding and knowledge of wildlife restraint and the tools involved.

Safety

During chemical immobilization and capture operations, there are a few safety precautions that individuals involved should keep in mind (Jonkel 1993):

During chemical immobilization and capture operations, a wildlife veterinarian should be consulted and part of the team. Federal regulations require that research facilities and entities, animal dealers and exhibitors have an attending veterinarian to consult and provide guidance on capture and chemical immobilization procedures and techniques.

The handling of all captured animals should be performed in a careful manner and as expediently as possible. This is to ensure that no trauma, behavioral distress, or unnecessary discomfort can occur. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determines what drugs can be used on certain animals. The FDA also requires a registration certificate for those using controlled substances; these can be obtained through the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Personnel or field technicians who may be using or even administering controlled drugs must be working under the supervision of a certificate holder. The certificate holder is also the party responsible for keeping detailed logs, and ensuring proper storage for all drugs. Individually, some states have strict veterinary codes which should be adhered to by anyone participating or engaging in the immobilization and capture of wild animals through chemical (drug) means.

Taking part in captures using chemical immobilization is dangerous, and any individual who immobilizes or takes part in a chemical immobilization is assuming a great deal of responsibility. Each time capture operations take place, two questions should be asked:

- What procedure or technique will produce the least hazard?

- Who is the most qualified to accomplish the task in the least amount of time with the least amount of stress to the animal?

In order for capture and immobilization to go smoothly, any individual involved needs to know his or her duty in the operation. This includes having a well-rounded understanding and knowledge of wildlife restraint and the tools involved.

Safety

During chemical immobilization and capture operations, there are a few safety precautions that individuals involved should keep in mind (Jonkel 1993):

- Do not make yourself or others involved available to the bear

- You should approach every trapping and capture as if you do not have the protection of a firearm

- Before trapping, and capture operations, evaluate the situation at hand and look at all potential and possible outcomes

Capture Techniques: Culvert/Box Traps

For our particular scenario, when capturing bears, the most common method is using culvert style traps in the Greater Yellowstone. These traps can be constructed with 14-gauge culvert sections, 1.8-2.4 meters in length and 1.2 meters wide, with a steel drop door at either one, or both ends. Bait is often times placed in proximity to the trigger for the trap, which will close the door behind the animal, keeping them contained.

For our particular scenario, when capturing bears, the most common method is using culvert style traps in the Greater Yellowstone. These traps can be constructed with 14-gauge culvert sections, 1.8-2.4 meters in length and 1.2 meters wide, with a steel drop door at either one, or both ends. Bait is often times placed in proximity to the trigger for the trap, which will close the door behind the animal, keeping them contained.

Anesthesia

The following criteria should be taken into account when selected the type of anesthesia that is used on bears (Jonkel 1993):

When a bear has been successfully immobilized, individuals managing capture operations should check for signs of arousal every 10 minutes as a rule of thumb. Signs of recovery that should be watched for include: head and paw movement, nose twitching, lip movement, and reaction to sounds. Generally, a bear will begin to recover about 20-30 minutes after it first raises its head.

The following criteria should be taken into account when selected the type of anesthesia that is used on bears (Jonkel 1993):

- Depresses the nervous system; animal is oblivious to pain and discomfort

- Places the bear in a deep sleep

- No serious side effects for the bear

- Short Induction period

- Down time of 1-3 hours

- Able to drug large bears with small quantity

- Drug utilized has an antidote for reversal

- Wide safety margin

When a bear has been successfully immobilized, individuals managing capture operations should check for signs of arousal every 10 minutes as a rule of thumb. Signs of recovery that should be watched for include: head and paw movement, nose twitching, lip movement, and reaction to sounds. Generally, a bear will begin to recover about 20-30 minutes after it first raises its head.

Selection of chemical immobilizing agents:

It is important to note that when selecting drugs for immobilization, that there is no “cookie cutter” drug that works for all wildlife; it is not a one size fits all equation. It is dually important to note that no individual drugs meets all of the safety requirements and level of effectiveness for all animals. Most drugs will be administered through intramuscular (IM) injection, which in the present day, are delivered by means of darts and dart guns. An ideal drug will be in a high enough concentration, that the risk for bruising and or muscle tearing during the liquid pressure injection is minimized.

Some of the drugs used during chemical immobilization are the following:

Narcotic Analgesics

Dissociative Anesthetics

Non-Narcotic Sedatives

Tranquilizers

Antagonists (reversal drugs)

Newest immobilizing drug is referred to as “BAM” consisting of Butorphanol, Azarperone and Medetomidine mix. BAM is effective in a wide variety of species and known for a quick knockdown and antagonists provide smoother and more rapid recovery than ketamine or telazol combinations.

Miscellaneous

It is important to note that when selecting drugs for immobilization, that there is no “cookie cutter” drug that works for all wildlife; it is not a one size fits all equation. It is dually important to note that no individual drugs meets all of the safety requirements and level of effectiveness for all animals. Most drugs will be administered through intramuscular (IM) injection, which in the present day, are delivered by means of darts and dart guns. An ideal drug will be in a high enough concentration, that the risk for bruising and or muscle tearing during the liquid pressure injection is minimized.

Some of the drugs used during chemical immobilization are the following:

Narcotic Analgesics

- Etorphine HCl – Antagonist: Naxolone Hydrochloride (HCl)

- Carfentanil citrate – Antagonist: Naxolone Hydrochloride (HCl)

- Thiofentanil A3080 – Antagonist: Naltrexone

Dissociative Anesthetics

- Ketamine Hydrochloride (HCl) “Ketaset” – Antagonist: Yohimbe Hydrochloride (HCl)

- Most versatile drug for animal immobilization and capture

- Often painful with injection

- Seizure can result when used alone

- Schedule III

- Tiletamine Hydrochloride (HCl) and Zolazepam Hydrochloride (HCl) “Telazol or CI-744” – Antagonist: Doxapram Hydrochloride (HCl)

- 2.5 times more potent than ketamine; wide safety margin

- Schedule III drug

Non-Narcotic Sedatives

- Xylazine Hydrochloride (HCl) – Antagonist: Yohimbe Hydrochloride (HCl)

- Ungulates are very sensitive to xylazine

- Often induces vomiting

- Dexmedetomidine “Dexdomitor” – Antagonist: Atipamazole

- 10-20 times more potent than xylazine

- Butorphanol**

- Enhances xylazine effects and improves the quality of immobilization

- Ungulates: add 0.05 – 0.1 mg/kg & Carnivores: add 0.2 mg/kg

Tranquilizers

- Acepromazine Maleate (Acepromazine) – Antagonist: None known

- Diazepam “Valium” – Antagonist: None known

Antagonists (reversal drugs)

- Naxolone Hydrochloride “Naxolone or Narcan”

- Yohimbe Hydrochloride “Yohimbe”

- Doxapram Hydrochloride “Doxapram”

- Tolazoline

- Atipamazole “Antisedan”

Newest immobilizing drug is referred to as “BAM” consisting of Butorphanol, Azarperone and Medetomidine mix. BAM is effective in a wide variety of species and known for a quick knockdown and antagonists provide smoother and more rapid recovery than ketamine or telazol combinations.

Miscellaneous

- Atropine sulfate (reduces salivation, sweating, stabilizes heart rate)

- Succinylcholine Chloride “Sucostrin or Anectine”

Telazol

The combination of tiletamine and zolazepam forms a drug known as Telazol. Tiletamine alone has been known to cause seizures; mixing zolazepam with tiletamine, which is an anti-convulsant and muscle relaxer, can limit side effects and allow for smoother knockdown. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) uses Telazol most commonly because of its wide safety margin, least variability in comparison to other drugs, and because it is the safest and most humane (Jonkel 1993). The standard established for Telazol use by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team is 250 mg per 100 lbs.; additional Telazol may be administered if needed via intramuscular hand injection. The dosage established for Telazol is 1 ml/100lbs. Telazol has been determined to be safer than other drugs used in wildlife capture, such as ketamine. Telazol is ultimately safer than ketamine; anesthesia using this drug does not have to be monitored or checked. Bears generally come out of this anesthesia slowly, and there have been no documented cases (in literature according to Jonkel 1993) of explosive or spontaneous arousal. One advantage to Telazol is it can be mixed in high concentrations and delivered in small volumes. Telazol is cycled through a bears body rapidly in comparison to other drugs. However, occasionally bears will fail to respond to chemical restraint. The average induction time using Telazol on a bear is 3-8 minutes (Taylor et al. 1988, Haroldson 1988) and typically the bear will remain anesthetized for 45-211 minutes. Bears that are deeply sedated and immobilized generally will completely recover anywhere between 3-4 hours (Taylor et al. 1988, Amstrup 1987). As stated previously, one of many things to be considered when selecting anesthesia is whether there is a potential antagonist, or antidote for reversal. While not a true antagonist, Doxapram hydrochloride or Dopram can be used to counter the effects of Telazol at 2.5 mg per lbs.

The combination of tiletamine and zolazepam forms a drug known as Telazol. Tiletamine alone has been known to cause seizures; mixing zolazepam with tiletamine, which is an anti-convulsant and muscle relaxer, can limit side effects and allow for smoother knockdown. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) uses Telazol most commonly because of its wide safety margin, least variability in comparison to other drugs, and because it is the safest and most humane (Jonkel 1993). The standard established for Telazol use by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team is 250 mg per 100 lbs.; additional Telazol may be administered if needed via intramuscular hand injection. The dosage established for Telazol is 1 ml/100lbs. Telazol has been determined to be safer than other drugs used in wildlife capture, such as ketamine. Telazol is ultimately safer than ketamine; anesthesia using this drug does not have to be monitored or checked. Bears generally come out of this anesthesia slowly, and there have been no documented cases (in literature according to Jonkel 1993) of explosive or spontaneous arousal. One advantage to Telazol is it can be mixed in high concentrations and delivered in small volumes. Telazol is cycled through a bears body rapidly in comparison to other drugs. However, occasionally bears will fail to respond to chemical restraint. The average induction time using Telazol on a bear is 3-8 minutes (Taylor et al. 1988, Haroldson 1988) and typically the bear will remain anesthetized for 45-211 minutes. Bears that are deeply sedated and immobilized generally will completely recover anywhere between 3-4 hours (Taylor et al. 1988, Amstrup 1987). As stated previously, one of many things to be considered when selecting anesthesia is whether there is a potential antagonist, or antidote for reversal. While not a true antagonist, Doxapram hydrochloride or Dopram can be used to counter the effects of Telazol at 2.5 mg per lbs.

Calculating Drug Doses: Bears

Grizzly Bear: for this example we will be using Tiletamine HCl and Zolazepam HCl or known as “Telazol”

Estimated weight of the animal: 300lbs or 136kg

Dosage of drug: 4mg/kg

Concentration of drug:100mg/ml

Dosage for animal: 136kg x 4mg/kg = 544mg

Volume of the drug needed: 544mg/ 100mg/ml = 5.4ml

Grizzly Bear: for this example we will be using Tiletamine HCl and Zolazepam HCl or known as “Telazol”

Estimated weight of the animal: 300lbs or 136kg

Dosage of drug: 4mg/kg

Concentration of drug:100mg/ml

Dosage for animal: 136kg x 4mg/kg = 544mg

Volume of the drug needed: 544mg/ 100mg/ml = 5.4ml

Drug Delivery Systems

There are various methods of delivery for chemically immobilizing wild animals. Some of these include hand held syringes, jab stick or pole syringe, and projected darts or syringes. In the case of using hand held syringes, animals are often captured and restrained using nets. This method is ideal for deer, elk, goats and sheep. Jab sticks and pole syringes extend the length of the hand for administering the immobilizing drugs. Bears are often caught in culvert traps; the jab stick or pole syringe allows extension of the hand into the trap for delivery. Often times, bears will attempt to bite or break off the syringe, causing damage to it. Most jab sticks and pole syringes which are commercially manufactured and produced, have a guard around the needle protecting it until it makes contact with the animal. Projected darts and syringes are among some of the most common of modern day delivery systems. Dart guns utilize pressured carbon dioxide to deliver the dart or syringe to the animal. In short, the distance these guns can be fired is variable; personnel and technicians utilizing these means of delivery should practice before using on live animals. Among delivery systems not listed is the blow gun, which is silent and causes very little trauma to the animal on the receiving end. The disadvantage to this system is that is relies on close proximity and human air pressure (mouth piece).

There are various methods of delivery for chemically immobilizing wild animals. Some of these include hand held syringes, jab stick or pole syringe, and projected darts or syringes. In the case of using hand held syringes, animals are often captured and restrained using nets. This method is ideal for deer, elk, goats and sheep. Jab sticks and pole syringes extend the length of the hand for administering the immobilizing drugs. Bears are often caught in culvert traps; the jab stick or pole syringe allows extension of the hand into the trap for delivery. Often times, bears will attempt to bite or break off the syringe, causing damage to it. Most jab sticks and pole syringes which are commercially manufactured and produced, have a guard around the needle protecting it until it makes contact with the animal. Projected darts and syringes are among some of the most common of modern day delivery systems. Dart guns utilize pressured carbon dioxide to deliver the dart or syringe to the animal. In short, the distance these guns can be fired is variable; personnel and technicians utilizing these means of delivery should practice before using on live animals. Among delivery systems not listed is the blow gun, which is silent and causes very little trauma to the animal on the receiving end. The disadvantage to this system is that is relies on close proximity and human air pressure (mouth piece).

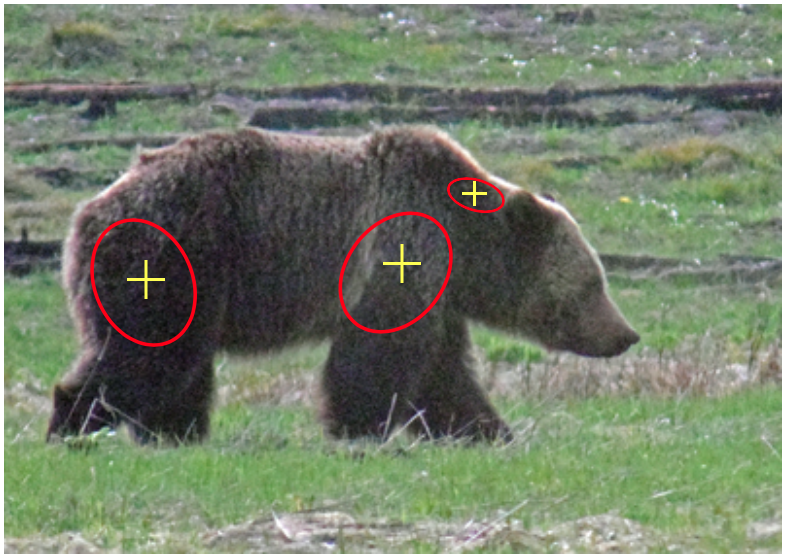

Target Areas when Darting

During the fall and early spring, grizzlies (especially males) can have an enormous amount of fat on their hinder quarters, sometimes even reaching 5 inches thick. When preparing and planning to dart and immobilize a bear, it is important to aim for a large muscle masses, generally at the center of these groups (neck, front shoulder). It is important to take into consideration that these areas are capable of draining infection quickly (Jonkel 1993).

During the fall and early spring, grizzlies (especially males) can have an enormous amount of fat on their hinder quarters, sometimes even reaching 5 inches thick. When preparing and planning to dart and immobilize a bear, it is important to aim for a large muscle masses, generally at the center of these groups (neck, front shoulder). It is important to take into consideration that these areas are capable of draining infection quickly (Jonkel 1993).

Post Immobilization Care

When an animal is first immobilized, make sure airways of the animal are unobstructed (vomit, foreign matter). The first procedure you should perform when the animal is in hand is a physical exam. For every animal, a custom exam plan should be established, including TPR or temperature, pulse and respiration. You should focus on guiding the animals body temperature and not reacting to it. Capillary Refill Time (CRT) is also important to monitor. This involves pressing on the gums above the canines (predators) or on the dental pad of ungulates; a healthy refill time is 2 seconds. While a pulse oximeter is not required, using one is strongly encouraged. The individuals involved in immobilizing the animal have the primary obligation to ensure the physical well-being and health of the animal in hand. If at any point, deteriorating conditions present themselves, the animals’ health takes priority over sample collection and or research. An animal should never be left alone until it has fully recovered from immobilization. All staff and technicians should position themselves in a safe position during the recovery of the animal. Coordinate with the attending veterinarian whether antibiotics are needed after capture. For carnivores, sometimes “dual penicillin” with Procaine Pen G and Benzathine are used to prevent infection (for ungulates, oxytetracycline). Bears depend on gut flora for hibernation and because of this, some veterinarian err on the side of caution and recommend to avoid giving antibiotics to bears at all.

Antibiotics and their use

It is important that those handling bears and wildlife in general are familiar with the appropriate antibiotics to give when a situation warrants their use. In general, antibiotics should not be given to every bear. It is completely unnecessary and does not have any benefit (Jonkel 1993). Situations that warrant the use of antibiotics may include infection, intensive surgery, or a serious wound inflicted during capture or discovered during capture; antibiotics would benefit a bear in all of these outlined situations. The recommended antibiotic for bears is LA-200 or known as oxytetracycline. The dosage is 100 mg/22lbs (Jonkel 1993); this can be doubled if there is injury or an infection of serious nature. An important consideration when using LA-200 is that it is often times painful during injection; you may spread out injections to multiple sites. It should be mentioned, that Dual-Pen is another common antibiotic that some wildlife professional may use in place of LA-200.

When an animal is first immobilized, make sure airways of the animal are unobstructed (vomit, foreign matter). The first procedure you should perform when the animal is in hand is a physical exam. For every animal, a custom exam plan should be established, including TPR or temperature, pulse and respiration. You should focus on guiding the animals body temperature and not reacting to it. Capillary Refill Time (CRT) is also important to monitor. This involves pressing on the gums above the canines (predators) or on the dental pad of ungulates; a healthy refill time is 2 seconds. While a pulse oximeter is not required, using one is strongly encouraged. The individuals involved in immobilizing the animal have the primary obligation to ensure the physical well-being and health of the animal in hand. If at any point, deteriorating conditions present themselves, the animals’ health takes priority over sample collection and or research. An animal should never be left alone until it has fully recovered from immobilization. All staff and technicians should position themselves in a safe position during the recovery of the animal. Coordinate with the attending veterinarian whether antibiotics are needed after capture. For carnivores, sometimes “dual penicillin” with Procaine Pen G and Benzathine are used to prevent infection (for ungulates, oxytetracycline). Bears depend on gut flora for hibernation and because of this, some veterinarian err on the side of caution and recommend to avoid giving antibiotics to bears at all.

Antibiotics and their use

It is important that those handling bears and wildlife in general are familiar with the appropriate antibiotics to give when a situation warrants their use. In general, antibiotics should not be given to every bear. It is completely unnecessary and does not have any benefit (Jonkel 1993). Situations that warrant the use of antibiotics may include infection, intensive surgery, or a serious wound inflicted during capture or discovered during capture; antibiotics would benefit a bear in all of these outlined situations. The recommended antibiotic for bears is LA-200 or known as oxytetracycline. The dosage is 100 mg/22lbs (Jonkel 1993); this can be doubled if there is injury or an infection of serious nature. An important consideration when using LA-200 is that it is often times painful during injection; you may spread out injections to multiple sites. It should be mentioned, that Dual-Pen is another common antibiotic that some wildlife professional may use in place of LA-200.

Radio-collaring

The Craighead brothers were the pioneers of radio telemetry during the 1960’s, when they first instrumented and collared grizzly bears for monitoring in Yellowstone National Park. Since then, radio telemetry has been an invaluable tool for bear research and management. Some uses for telemetry have contributed to research regarding habitat requirements, food habits, daily movements, home ranges, population dynamics, behavior, and human and bear relationships.

Since the days of the Craighead brothers, radio telemetry and closely related technology has been constantly developing and methodologies constantly improving. Aside from the traditional VHF collars used by the Craighead’s, researchers now have collars which are satellite connected, use GPS, video; some collars even have the unique ability to immobilize an animal or bear upon an initiated radio signal (dart collars).

Due to the cost of telemetry and the associated equipment, it is imperative, essential and critically important that bears are correctly fitted and instrumented when collared. This can ensure the maximum data obtained, plus minimizing any discomfort or unnecessary stress to the bear involved.

There are several important precautions that an individual should take when attaching a collar to an animal, specifically a bear. The collar should not in any way, restrict or alter the breathing of the bear, nor should it interfere or alter day-to-day activities, or behavior. Collars should be attached in a manner where they cause little to any discomfort; this is particularly important when attaching satellite GPS and video collars, which are seemingly bulky. Collars are prone to rotating and moving around a bears neck during feeding, or physical activity. This quirk causes a slight impediment when utilizing darting collars, which inject an immobilizing drug to the bear activated by radio signal (Mech et al. 1984). Each and every collar deployed should have enough space to allow adequate air circulation to the neck. A collar that is fixed too tight may cause irritation, chaffing, and eventual open sores, potentially leading to infection. A collar should be attached so it can expand as a bear grows; it should be able to release and fall off should it become too tight. Collars deployed should be attached with a system in place that allows it to break/fall off every 2-3 years (commanded release, or break away collars).

Tattooing

Tattoos have been widely used in the wildlife community for identification. They help during mark recapture operations when an individual needs to be documented as a recapture or new individual. It is important to maintain a clean environment when tattooing an animal, and to only use sterile instruments.

Emergencies which can arise during chemical immobilization processes include the following (brief overview):

The Craighead brothers were the pioneers of radio telemetry during the 1960’s, when they first instrumented and collared grizzly bears for monitoring in Yellowstone National Park. Since then, radio telemetry has been an invaluable tool for bear research and management. Some uses for telemetry have contributed to research regarding habitat requirements, food habits, daily movements, home ranges, population dynamics, behavior, and human and bear relationships.

Since the days of the Craighead brothers, radio telemetry and closely related technology has been constantly developing and methodologies constantly improving. Aside from the traditional VHF collars used by the Craighead’s, researchers now have collars which are satellite connected, use GPS, video; some collars even have the unique ability to immobilize an animal or bear upon an initiated radio signal (dart collars).

Due to the cost of telemetry and the associated equipment, it is imperative, essential and critically important that bears are correctly fitted and instrumented when collared. This can ensure the maximum data obtained, plus minimizing any discomfort or unnecessary stress to the bear involved.

There are several important precautions that an individual should take when attaching a collar to an animal, specifically a bear. The collar should not in any way, restrict or alter the breathing of the bear, nor should it interfere or alter day-to-day activities, or behavior. Collars should be attached in a manner where they cause little to any discomfort; this is particularly important when attaching satellite GPS and video collars, which are seemingly bulky. Collars are prone to rotating and moving around a bears neck during feeding, or physical activity. This quirk causes a slight impediment when utilizing darting collars, which inject an immobilizing drug to the bear activated by radio signal (Mech et al. 1984). Each and every collar deployed should have enough space to allow adequate air circulation to the neck. A collar that is fixed too tight may cause irritation, chaffing, and eventual open sores, potentially leading to infection. A collar should be attached so it can expand as a bear grows; it should be able to release and fall off should it become too tight. Collars deployed should be attached with a system in place that allows it to break/fall off every 2-3 years (commanded release, or break away collars).

Tattooing

Tattoos have been widely used in the wildlife community for identification. They help during mark recapture operations when an individual needs to be documented as a recapture or new individual. It is important to maintain a clean environment when tattooing an animal, and to only use sterile instruments.

Emergencies which can arise during chemical immobilization processes include the following (brief overview):

- Hypothermia and hyperthermia

- Shock

- Bloat (ungulates)

- Inhalation of stomach contents (ungulates)

- Seizures

- Capture myopathy

Specific to Grizzly Bears

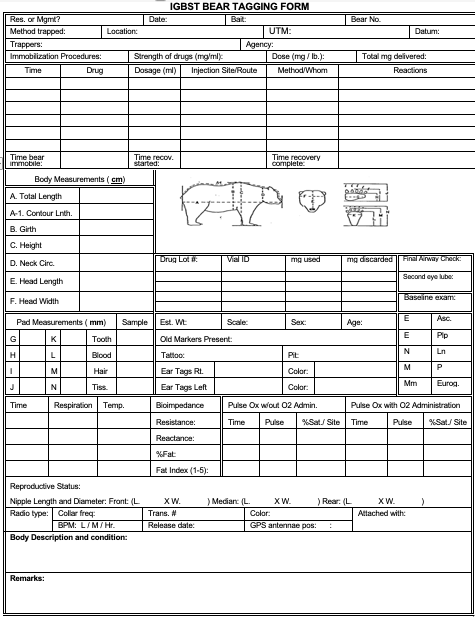

The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) is the responsible entity for research conducted on grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). The IGBST has their own specific handling protocol and prescription drug protocol when handling bears. “All research animals are handled by following the specific requirements of USGS Animal Care and Use policies.”

Below are some of the specific criteria outlined in their existing protocols. Information provided on chemical immobilization is on XZT and Telazol as they are the most commonly used drugs in grizzly bears by the IGBST.

The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) is the responsible entity for research conducted on grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). The IGBST has their own specific handling protocol and prescription drug protocol when handling bears. “All research animals are handled by following the specific requirements of USGS Animal Care and Use policies.”

Below are some of the specific criteria outlined in their existing protocols. Information provided on chemical immobilization is on XZT and Telazol as they are the most commonly used drugs in grizzly bears by the IGBST.

IGBST Prescription Drugs:

All anesthetized bears must have anchor snares attached (this is attached to an extremity, likely a leg). All anesthetized animals are to have a baseline physical exam recorded on capture form. Periodic evaluations of temperature, pulse, respiration, mucous membrane color/capillary refill time and airway should be as frequent as possible. All anesthetized animals are to have supplemental oxygen administered. The reversible anesthesia XZT (Xylazine/Telazol) should be considered among the first options. Other regimes should be considered as secondary options and used only on specific captures.

Xylazine/Telazol (XZT) IM injection:

Telazol by intramuscular (IM) injection (3.2-3.6 mg/lb)

All anesthetized bears must have anchor snares attached (this is attached to an extremity, likely a leg). All anesthetized animals are to have a baseline physical exam recorded on capture form. Periodic evaluations of temperature, pulse, respiration, mucous membrane color/capillary refill time and airway should be as frequent as possible. All anesthetized animals are to have supplemental oxygen administered. The reversible anesthesia XZT (Xylazine/Telazol) should be considered among the first options. Other regimes should be considered as secondary options and used only on specific captures.

Xylazine/Telazol (XZT) IM injection:

- 2.3 mg/lb

- 1.1 ml of Xylazine (300mg/ml) plus 1.0 ml sterile water per vial of Telazol

- Concentration mg/ml: 132 mg Xylazine plus 200 mg Telazol

- Dosage mg/lb: 0.9 mg Xylazine plus 1.4 mg Telazol

- Antagonist: Yohimbe for Xylazine (.05-.07 mg/lb or IV) OR Atipamazole (0.09 mg/lb, ½ IM- ½ IV)

- Administer the antagonist no sooner than 60 minutes post induction injection

- Note: Administer Atropine Sulfate (.02 mg/lb) for the prevention of bradycardia for all bears anesthetized with Alpha-2 agonists (Xylazine or metatomidine or their combinations).

- Note: Be prepared for spontaneous arousal of all bears anesthetized with alpha-2 agonists

- Provide ophthalmic ointment immediately upon the removal from trap and prior to departing the animal

Telazol by intramuscular (IM) injection (3.2-3.6 mg/lb)

Baselines:

Temperature: want between 98-102°F

Pulse: strong & consistent, not thread & weak

Heart Rate: try left side of sternal animal at 4-5th rib; want between 50-120/min

Respiration: want between 12-20/min; listen to airway from front to back, listen for collapsed lung

Capillary Refill: test gums, lips, eyelids; want <= 2 second refill

Endotracheal tube: lube the tube, measure to shoulder or a shorter distance, pull tongue forward and open mouth wide open, see the opening to the airway, insert, inflate, tie off, use jaw spreader, don’t use if aspiration has already occurred. Tubes that are too deep may occlude a brachial tube. Listen for free passage of air.

Physical Exam:

Eyes: test level of sedation-pupil dilation; test blood pressure & shock-want pink underside of eyelid; look for injuries; debris; test for dehydration- pinch, apply ophthalmic ointment

Ears: test levels of sedation-movement; look for wounds (flush or stitch); look for infections-redness (give antibiotics); look for gross trauma and parasites

Nose: check airway, look for blood, injuries, gross trauma

Mouth: test blood profusion by capillary refill; test level of sedation-jaw rigidity; test hydration-moisture levels in mouth; test airway-look for obstructions or vomit, look for injuries, blood, throat cancer, look for jaw-dislocation & examine symphysis; look for new or old tooth fractures

Airway: look for obstructions or vomit, look for injuries, blood

Mucous membranes: assess capillary refill. Should be less than 2 seconds. Assess color and trend. Get good baseline. Auscultation. Listen with stethoscope for pulse and lung fiels. Know normal

Lymph nodes: look for swelling (indicates infections)

Palpitation of Body, Joints, Limbs, Feet: feel for crepitation, fractures, swelling, new or old wounds; disarticulations, fractures, bruises, distensions

Pulse: attempt to check peripheral pulse for rate and quality. Know baseline

Urogenital: check sex, estrus status, evidence of lactation and parasites

REMINDER: Steroids may be abortifactive for gravid females; be willing to live by the consequences. Use only in life threatening circumstances for pregnant females.

Sources Cited

Amemo et. al. AAZV proceedings Sept 2001 Orlando, FL (2001)

Cattet et. al. Ursus14 (1) 88-93 (2003)

Reynolds et. al. J. Wildl. Manage. 53(4) 916-978 (1989)

Krieger and Arnemo, Handbook of wildlife Immobilization. (2002)

Plumb Veterinary Manual (2Cr03)

Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Formulary. Fort Collins, co. (1gg5)

Animal Medical Center Formulary. New york, Ny. (1995)

Merck Veterinary Manual, Rahway, NJ (2003)

Bookhout, T. A. (1996). Research and management techniques for wildlife and habitats (No. 639.9 R4).

Johnson, M.R. (2017). Wildlife Handling and Chemical Immobilization for Researchers and Managers. Global Wildlife Resources.

Jonkel, J. L. (1993). A manual for handling bears for managers and researchers. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Grizzly Bear Recovery.

Temperature: want between 98-102°F

Pulse: strong & consistent, not thread & weak

Heart Rate: try left side of sternal animal at 4-5th rib; want between 50-120/min

Respiration: want between 12-20/min; listen to airway from front to back, listen for collapsed lung

Capillary Refill: test gums, lips, eyelids; want <= 2 second refill

Endotracheal tube: lube the tube, measure to shoulder or a shorter distance, pull tongue forward and open mouth wide open, see the opening to the airway, insert, inflate, tie off, use jaw spreader, don’t use if aspiration has already occurred. Tubes that are too deep may occlude a brachial tube. Listen for free passage of air.

Physical Exam:

Eyes: test level of sedation-pupil dilation; test blood pressure & shock-want pink underside of eyelid; look for injuries; debris; test for dehydration- pinch, apply ophthalmic ointment

Ears: test levels of sedation-movement; look for wounds (flush or stitch); look for infections-redness (give antibiotics); look for gross trauma and parasites

Nose: check airway, look for blood, injuries, gross trauma

Mouth: test blood profusion by capillary refill; test level of sedation-jaw rigidity; test hydration-moisture levels in mouth; test airway-look for obstructions or vomit, look for injuries, blood, throat cancer, look for jaw-dislocation & examine symphysis; look for new or old tooth fractures

Airway: look for obstructions or vomit, look for injuries, blood

Mucous membranes: assess capillary refill. Should be less than 2 seconds. Assess color and trend. Get good baseline. Auscultation. Listen with stethoscope for pulse and lung fiels. Know normal

Lymph nodes: look for swelling (indicates infections)

Palpitation of Body, Joints, Limbs, Feet: feel for crepitation, fractures, swelling, new or old wounds; disarticulations, fractures, bruises, distensions

Pulse: attempt to check peripheral pulse for rate and quality. Know baseline

Urogenital: check sex, estrus status, evidence of lactation and parasites

REMINDER: Steroids may be abortifactive for gravid females; be willing to live by the consequences. Use only in life threatening circumstances for pregnant females.

Sources Cited

Amemo et. al. AAZV proceedings Sept 2001 Orlando, FL (2001)

Cattet et. al. Ursus14 (1) 88-93 (2003)

Reynolds et. al. J. Wildl. Manage. 53(4) 916-978 (1989)

Krieger and Arnemo, Handbook of wildlife Immobilization. (2002)

Plumb Veterinary Manual (2Cr03)

Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Formulary. Fort Collins, co. (1gg5)

Animal Medical Center Formulary. New york, Ny. (1995)

Merck Veterinary Manual, Rahway, NJ (2003)

Bookhout, T. A. (1996). Research and management techniques for wildlife and habitats (No. 639.9 R4).

Johnson, M.R. (2017). Wildlife Handling and Chemical Immobilization for Researchers and Managers. Global Wildlife Resources.

Jonkel, J. L. (1993). A manual for handling bears for managers and researchers. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Grizzly Bear Recovery.