|

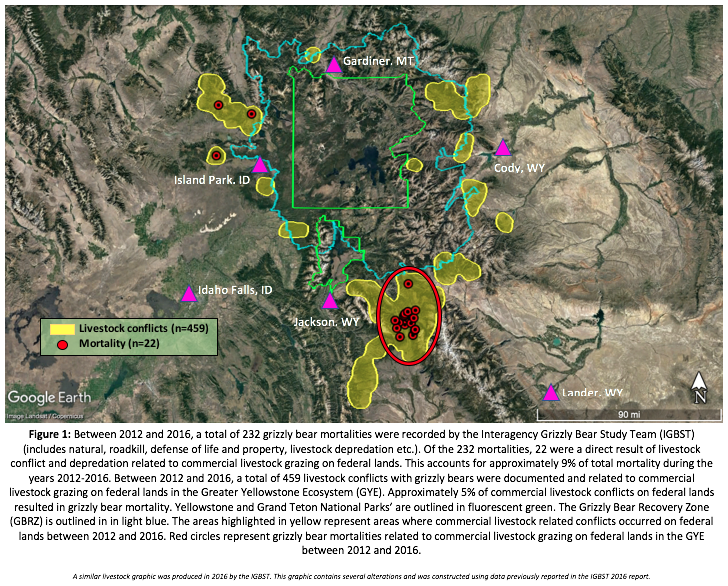

Example In the spotlight- Grizzly 781: During 2006, grizzly 781 was born in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). On June 11, 2009, at three-years old, 781 was captured, near Deadman Creek in the Shoshone National Forest (SNF). Grizzly 781 was not collared during this capture. Five-years would pass until he would again be captured, this time for management purposes. Unfortunately, the bear found himself in a far too common predicament: livestock depredation. Nearly 90 miles away from where he was initially captured in 2009, Grizzly 781 was the culprit of a cow mortality near Red Lodge, MT. He was captured and collared at Grove Creek, MT by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks and U.S. Department of Agriculture - Wildlife Services on July 15, 2014. He was relocated and released near Lodgepole Creek, MT near the Gallatin Range. Grizzly 781 cast his collar in September 2014 in the Gallatin National Forest. In 2018, grizzly 781 would be 12 years-old. The real question is: How can we prevent livestock depredation and avoid unnecessary grizzly bear mortality related to livestock grazing operations? What can we learn from grizzly 781 and other bears involved in livestock depredation? Livestock Conflict and Mortality: “Identifying the locations and causes of grizzly bear mortality is another key component in understanding the dynamics of this population. Over 80% of all documented bear mortalities are human-caused. Tracking human-caused bear deaths helps define patterns and trends that can direct management programs designed to reduce bear mortality.” – Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) Between the years 2012 and 2016, a total of 459 livestock conflicts with grizzly bears were documented and related to commercial livestock grazing on federal lands in the GYE. During these years, 22 of the 459 conflicts on federal lands resulted in grizzly bear mortality, which means 5% of these conflicts proved to be fatal for the bear involved. Over the 4-year span, the IGBST recorded a total 232 mortalities from all causes (natural, roadkill, defense of life and property, livestock conflict & depredation, etc.) Livestock related mortalities related to commercial livestock grazing on federal lands account for 9% of total mortality during 2012-2016. With over 80% of all documented mortalities resulting from us humans, it is important to find potential ways to mitigate and avoid grizzly bear conflict. Whether that is the deployment or implementation of electric fences, range riders, or even the easy implementation of bear spray for hunters and recreationalists, finding areas where mortality can be reduced is important. Livestock grazing operations have several options to prevent depredation or conflict with grizzly bears. In operations where rearing may occur, animals that give birth, must be securely confined, housed, and protected to reduce risk of bear attraction. The removal of all afterbirth and carcass materials is especially important. Electric barriers around confined livestock units are strongly encouraged for deterring bears. Fencing is an important component while protecting livestock. The implementation of electric wires into fencing is very effective at deterring bears. Electric fences should be composed of 9 wires and begin approximately 4 inches from the ground (Dohner, J. V., 2017). "Range riding" is another potential alternative to providing security to free-ranging livestock. Deceased cattle and livestock also serve as an attractant for grizzly bears. It is important for commercial livestock owners and operators to regularly remove or relocate any carcasses from areas containing "active" healthy livestock, to reduce the risk of depredation. In eligible counties within Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, Defenders of Wildlife will compensate 50% of the cost for electric fencing to prevent grizzly bear access to livestock, attractants (garbage, orchards, beehives). One important piece of information: notice on the map (Fig.1) the location of mortalities. During 2012-2016, 19 of 22 mortalities related to commercial livestock grazing on federal lands were located within a 15-mile radius of one another (near Wind River Range). A possible management consideration going into the future would be providing incentives for commercial livestock owners and agricultural operations who take precautionary and recommended measures to secure livestock and livestock attractants (grain, feed, etc.) Monitoring grizzly mortality and its origins are extremely important. Once a threatened species, protected under the endangered species act enforced by US Fish and Wildlife, killing a grizzly bear was prosecutable under federal law. In instances as these, US Fish and Wildlife was the responsible agency in investigating and prosecuting perpetrators responsible for unnecessary grizzly bear mortality. Still, post-delisting from these protections, state wildlife agencies such as Wyoming Game & Fish, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Idaho Fish and Game are now the responsible agencies for enforcing incidental or illegal harvest outside of the current proposed hunting period.

---Dohner, J. V. (2017). The Encyclopedia of Animal Predators: Protect Your Livestock, Poultry, and Pets; Identify the Tracks and Signs of More Than 30 Predators; Learn about Each Predator's Traits and Behaviors. Storey Publishing. ---Haroldson, M.A., Dickinson, C., Bjornlie, D.D. (2015). Bear Monitoring and Population Trend. Pages 5-11 in F.T. van Manen, M.A. Haroldson, and S.C. Soileau, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2014. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, Montana, USA. ---Grizzly Bear Habitat Modeling Team. (2017). 2016 Grizzly Bear Habitat Monitoring Report. Appendix A. Pages 95–117 in F. T. van Manen, M. A. Haroldson, and B. E. Karabensh, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2016. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, Montana, USA.

0 Comments

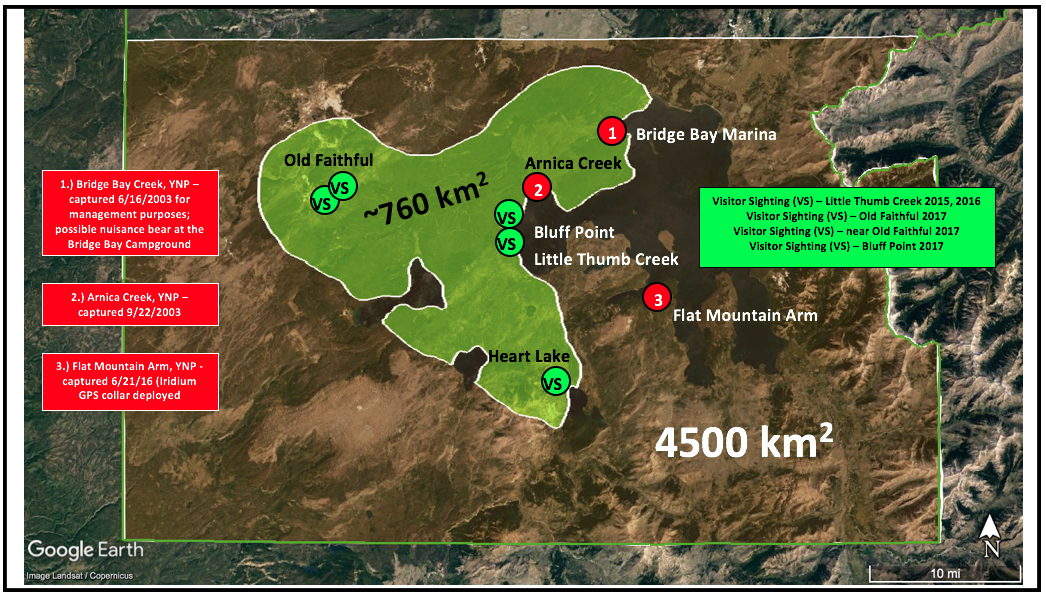

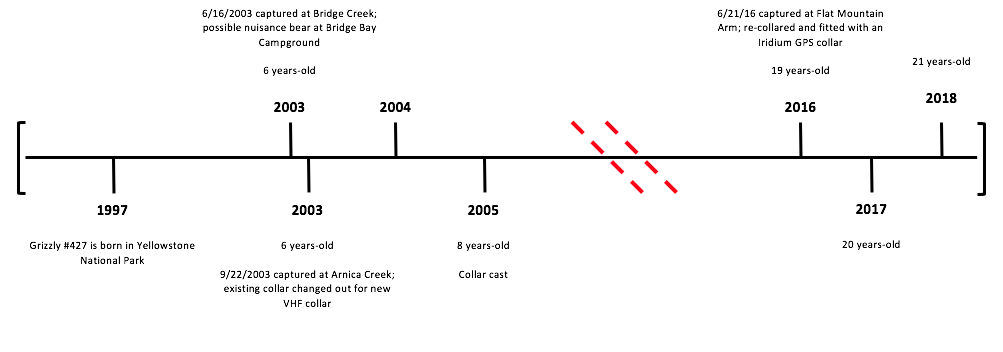

Yellowstone National Park is comprised of 3,472 mi2 (8991 km2), or 2,221,766 acres. The park’s boundaries lie 96% in the state of Wyoming, 3% in Montana and 1% in Idaho. Yellowstone has five park entrances, leading to 466 miles of road (310 miles paved). Less than 1% of Yellowstone’s landscape is covered by roads. In Yellowstone, there are approximately 150 (conservative) grizzly bears whose home ranges are completely, or partially inside of the park. Some areas of the park, roadways run through highly desired and preferred grizzly bear habitat. Some bears become habituated to human-presence by hanging along the roadsides. Habituation can be defined as when bears become accustomed and experience no threat from human activity consistently and frequently, they begin to expect the same pattern time and time again, and react with very little response (Knight and Cole 1995). Habituation is not always a terrible thing, especially with grizzly bears. Habituation will allow bears to use areas with high human presence and activity, which has been demonstrated to increase habitat effectiveness (Herrero et al. 2005). In Yellowstone, this sort of behavior is commonly observed, where some wildlife, and bears may be subject to seeing thousands, if not millions of visitors each year and over the course of their lifetime. In this sort of environment, bears will adapt and acclimate to the presence and activities of visitors if seen at a great enough frequency. Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Park’s beginning in the 1990’s shifted their focus from managing the bears, to managing the people. Instead of trapping, relocating, and hazing bears, park staff began to ensure that visitors were in compliance at bear jams and exhibiting predictable behavior. This strategy has been in place for 25 years (1990-2014) (Gunther et al. 2015). Over the past quarter century, both Yellowstone and Grand Teton have experience increasing levels of bear habituation in roadside habitats, leading to an increase in “bear-jams” (Haroldson & Gunther 2013). However, while habituation allows an increase in habitat effectiveness and allows for satisfying visitor experience, it does create a dangerous and unbeknownst situation for the wildlife, a double-edged sword. Bears and cars don’t mix typically. If bears become habituated, it can pose a risk for vehicle accidents. Habituation may not always be the case for grizzly presence near the roadways. Transient bears may use the roadways as a travel corridor, or even crossing to get from place to place. Sometimes after emerging from hibernation, bears may use the roads in an effort to conserve energy expenditure when snow is still deep (same with other wildlife such as bison). Between 2009 and 2018, 25 grizzly bears were documented road-kill mortalities by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). Of the 25 bears, 19 were male, 5 were female and 1 was unknown; 11 were subadults, 4 were yearlings, 3 cubs-of-the-year (COY), 6 adults, and 1 unknown. In Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) 4 grizzlies were documented and in Yellowstone National Park 4 grizzlies were documented. Outside of the national parks, 8 grizzlies were documented roadkill mortalities in Montana, 8 in Wyoming and 1 in Idaho. The IGBST reports that 80% of grizzly bear mortalities are human-caused. This includes but not limited to: roadkill, natural death, defense of life and property (DLP), hunting, mistaken identity (black bear hunt). From 2009 until 2018, 429 grizzlies have been documented mortalities, of which roadkill mortality accounts for approximately 6%. The other 94% consist of DLP, natural, hunting, mistaken identity. As visitation increases, it is likely (anecdotal) that roadkill mortalities may increase. More grizzlies on average are killed every year as a result of self-defense while hunting than motor vehicle accidents; this was the case between 2009-2018 (IGBST Annual Morality Reports 2009-2018) Ultimately, roadkill mortalities do not always fall back on motor vehicle operators. Instances have occurred, where a motor vehicle operator was doing everything correctly, and a bear darted in front of their vehicle. In rare cases, bears have even timed their crossing incorrectly and run into vehicles. Between 1989 and 1999, it was found that bears (grizzlies and black bears) were killed on roads with higher speed limits (Gunther & Biel 1999). It is important to note that it is not always the fault of the vehicle operator. While unfortunate, sometimes bears are unpredictable, and run across the roadway from thick brush or timber, allowing for little time to react. Chastising visitors involved in accidents which are out of their control is irresponsible. Focusing on inattentive and negligent operation of motor vehicles is a more beneficial initiative. Striking and killing a grizzly bear in YNP is rare, though, this does not mean it cannot happen. Another important consideration: not all bears struck and hit by vehicles die. It is a poor assumption that all bears involved in motor vehicle accidents perish. In recent years, bears have been struck by vehicles, later running off into the wilderness with minimal notable or documented injuries. Ex: 2002 -> grizzly bear #125, accompanied by 2 COY, was struck by a vehicle just north of Canyon Junction in YNP, causing her collar to drop; the severity of her injuries was unknown at the time. Four years later in 2006, she was alive and well, captured and collared again at Antelope Creek in YNP. 2010 -> Mary Mountain Trailhead, Hayden Valley, YNP: a female grizzly with 3 cubs was struck during late May; Bear Management closed Mary Mountain Trail temporarily and investigated, but found no signs of a mortality. Ultimately, when traveling on roads in YNP and GTNP, be conscientious of your surroundings. Sometimes, the beauty of the landscape, or even nearby wildlife may blind us from focusing our attention on the road while driving. Sometimes, we may occasionally find ourselves speeding. Ultimately, it is the role and responsibility of every visitor and motor vehicle operator to maintain complete control of your vehicle at all times. It is also your responsibility to inform park officials, or local fish & game authorities of wildlife/vehicle injuries and related accidents. Grizzly #427: Not many people are familiar with grizzly #427 in Yellowstone National Park. #427 calls south and central Yellowstone his home. Frequently throughout his life, he has been observed on various spawning streams surrounding Yellowstone Lake. He has been dubbed the infamous “Preacher Bear.” Few visitors have been given the opportunity to watch #427 in action as he fishes for Cutthroat Trout in Little Thumb Creek, or Arnica Creek. No matter the case, when #427 does emerge as a ‘ghost’ from the wilderness, he doesn’t disappoint. In past years, others have watched him furiously attempt to break through thick ice near Bluff Point, or even rip through an old overwintered carcass near Old Faithful. We really only have a little snapshot of #427 life, and that was by pure accident. He was suspected to be a possible nuisance bear in the Bridge Bay Campground area in Lake District, and was captured for management purposes on June 16, 2003 at 6 years-old. At the time he was captured, he was fitted with a radio collar, relocated, and later released. On September 22, 2003, he was captured at Arnica Creek, YNP. In 2005, #427 cast his collar. He would not be collared again until June 21, 2016, when he was captured at Flat Mountain Arm and fitted with a new radio collar. As of 2018, #427 is currently 21 years-old. Most bears in Yellowstone live to be 25-30 years old.  Figure 2: Known life history and range of grizzly #427 in Yellowstone National Park between 2003 and 2017. This map depicts areas where #427 has been captured and areas where visitors have submitted credible observations. The area highlighted and filled green is the area where 95%+ observations of #427 have been documented since 2003. The area highlighted in orange represents the area where #427 has been observed but infrequently. Grizzly #427 could use this area, but the exact use of this area is unknown unless referring to Iridium GPS data from 2016-present. Only visual observations from visitors during 2015-2017 are noted on this figure. This figure is not a representation of actual home range. A minimum convex polygon (MCP) would estimate #427 range approximately ~480 km2 between 2003-2017. Grizzly bear lineage: I had someone ask a few weeks ago if grizzly #211 (known to many as ‘Scarface’) had any descendents or offspring they could look for in the park. Now, with new advances in DNA, when the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) capture, collar and tag grizzlies, they also take DNA samples for reference. These can be compared against other samples into the future, and help identify genetic relatedness. The only bears that use to have DNA collected were those that had been handled and captured. Nowadays, DNA can be obtained via non-invasive methods such as 'hair snares' or 'hair corrals' which instigate the bear to rub against an object; the researcher can retrieve hair later and send it to the lab to be analyzed.

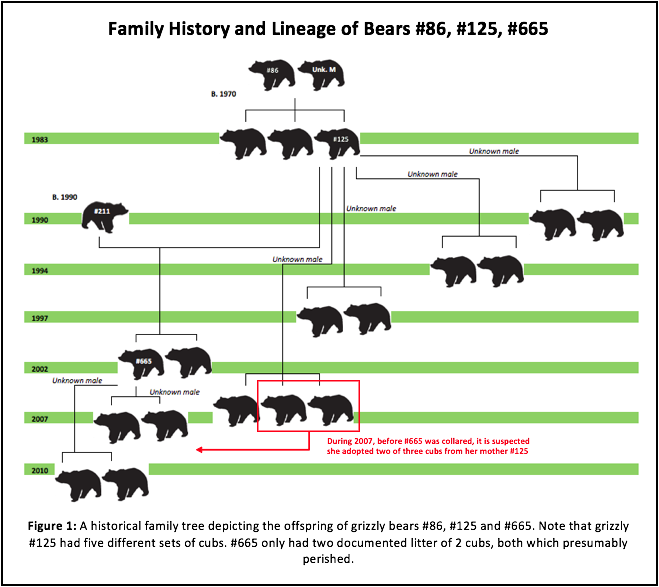

Based on information that has been gathered, there is one bear we know if the offspring of bear #211, and that is #665. Brief history: Grizzly bear #86 was born around 1970. On July 5, 1982, at age 12, she was captured at Antelope Creek, YNP; that year she was observed with no cubs. Two years later, July 5, 1984, she was captured again at Antelope Creek, YNP; this year, she was observed with three yearlings. In 1985, she booted all three offspring. One of those bears was #125. Grizzly #125 was first captured August 6, 1986 at Antelope Creek, YNP. She was captured again during July 1, 1990, that year observed with two cubs-of-the-year (COY). In 1991, she still had her two cubs as yearlings, and in 1992 she booted her two cubs at two-years old. In 1994, she was observed with her second litter of two COY. However, during the fall of 1995 when she was captured on October 13, neither cub was anywhere to be found. In 1997, her third litter of two COY was observed; during 1998 she had both cubs as yearlings. She would not have cubs again until 2002, where she for the fourth time, had a litter of two COY. One of those COY was grizzly #665. She would later be struck by a vehicle that year. #125 was again collared in 2006 at age 23 and was observed with three COY in 2007. That same year, #665 was observed with two COY (prior to collaring). Later during the year, #125 was observed with only 1 cub; #665, then unmarked, was observed with 4 cubs. It is suspected that #665 adopted her mother's (#125) cubs after they had been separated from her. #665 was involved in a management capture near the Yellowstone River in 2010, the perpetrator of chicken depredations. She was relocated to Arnica Creek with her two COY. At the time, DNA was confirmed she was the offspring of #125 and #211, making her the daughter of the late ‘Scarface.’ She received the nickname “the Dunraven sow,” as many observed her near Dunraven Pass. The following year, she unfortunately was observed with no offspring. She later dropped her collar on Halloween in 2011 near Sulfur Creek, YNP. The fate of #665 is unknown, and we may never know if she is alive, or deceased. Being 9 years old in 2011 would place her at about 16 years old. She could very well still be out in the wilds of Yellowstone. If you have purchased a grizzly chart, one thing that you should know! One the photo identification side, two ID numbers are flip flopped! Grizzly F10 should be F06.....and F06 should be F10. The grizzly F10 is commonly known to many as "Quad-mom." The numbers listed on the map are correct!

Please let me know if you have any questions! Thanks! |

AuthorTyler Brasington is a native born and raised Pennsylvanian, yet proud current Wisconsin resident. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater with a B.S. in Environmental Science. Currently, Tyler is pursuing his masters in Natural Resources with the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He has worked in Yellowstone National Park under the guidance and supervision of Dr. George Clokey and Dr. Jim Halfpenny. Disclaimer: The information and views expressed on this page do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Interior, US Geological Survey, National Park Service or the United States Government.

The Greater Yellowstone Grizzly Project

www.yellowstonegrizzlyproject.org © 2021 Tyler Brasington All rights reserved. No portion of this website may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, or appropriate authors, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. For permissions contact: [email protected] Archives

February 2021

Categories |

- Welcome

- Home

- About

- Submit sightings

- Family Tracker

- Publications & Research

- Natural Life History

- Cementum Age Determination for Grizzly Bears

- Nutrition & Diet

- Radio Telemetry and Wildlife Tracking

- Chemical Immobilization and Wildlife Handling

- Infectious Disease in Bears

- Effects of Wildfire on Grizzly Bears: Yellowstone 1988

- Mortality Database

- Photo gallery

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed