|

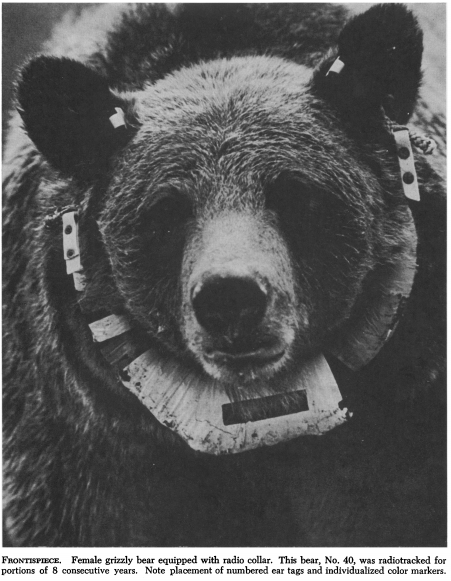

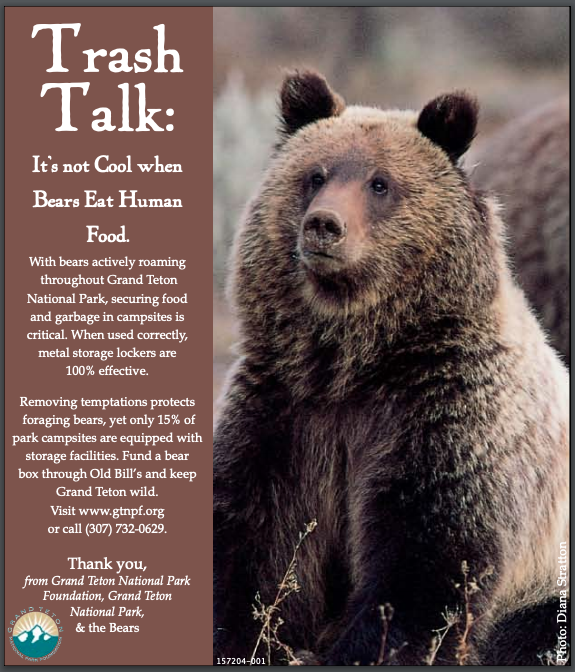

1. History of the Refuse Dumps in Yellowstone National Park As visitation and tourism increased in Yellowstone National Park, refuse and waste created directly from park visitors, lodging, and transportation posed a new problem. The park decided to create simple dump sites, often situated close to the origin of refuse and waste. Many of the refuse sites were extremely accessible to people (Otter Creek, Old Faithful) except for few (Trout Creek, Rabbit Creek). Two of the smaller dump sites, Otter Creek & Old Faithful, had concrete platforms where waste was dumped. A fence would separate the viewing bleachers from the area which the bears would feed. Specifically, at Otter Creek, rangers and park officials would provide educational and informational lectures about the bears known as "bear shows", until this practice ceased in 1942. Even though the "bear shows" had ended, the refuse sites remained active, allowing the park to handle increasing waste from visitation, and enabling bears to continue feeding at well-established and developed sites with predictable sources of food (Craighead et al. 1995).  Photos: Minor open areas, similar to scars (pictured above) are still left in the area of the Trout Creek refuse pit in Hayden Valley, YNP. You can still find some discarded soda bottles, old steel cans, and broken ceramics in the area where the dump use to be located. Even with the garbage dumps gone, bear activity is still extremely high in Hayden Valley. Major dumps were developed and positioned so that their visibility and accessibility was limited to the public, in a direct effort to not affect the public impression of the park and take away from its known aesthetic beauty. Some of the more notable dump sites from north to south include Gardiner, Cooke City, Tower Junction, West Yellowstone, Trout Creek, Rabbit Creek, Pelican Creek, and West Thumb.  Photos: The above images are all taken from where the Trout Creek refuse (garbage) dump once stood. Today, very few remnants are left behind to indicate any past presence of the dump site. Remaining relics such as old sardine cans, steel cans and glass soda bottles are the only remnants of Yellowstone's historic refuse dump past. The Trout Creek garbage dump was at the center of the Craighead's research in Hayden Valley. It is here they were able to observe the behavior of grizzlies, and collect census information pertaining to just how many bears occupied the area. The Craighead's collected census information and identified a rough number of individuals at most of the dump sites throughout (some on the periphery) of Yellowstone National Park. 2. Who were the Craighead brothers? In a nutshell: In 1958, John and Frank Craighead began their decade long study of grizzly bears in Yellowstone National Park. During this study, the Craigheads made initial advances in wildlife ecology, conservation, and management. They are responsible for pioneering the use of radio telemetry, chemical immobilization, and wildlife handling and population modeling (Craighead Institute, n.d.). The Craigheads were also responsible for the introduction of the ecosystem concept to wildlife management, as many of their findings demonstrated that grizzly bears were using a much larger area than just Yellowstone National Park (Craighead Institute, n.d.). In 1998, John Craighead received the Aldo Leopold Award. Both Frank & John were named among the top scientists in the country by the Audubon Society (Howard, 2016). Interestingly enough, both brothers attended Penn State University. Additionally, they worked for the Navy during World War II and were instrumental in developing a survival school and training program for the Navy's pilots; their survival guide was written in 1943 (Howard, 2016). Both Frank and John received their doctorates from the University of Michigan. John Craighead worked many decades at the University of Montana leading the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit (Howard, 2016). 3. Management Strategy Changes: Past & Present Before 1963, Yellowstone National Park had three criteria for managing black and grizzly bear populations, summarized by Craighead et al. 1995: 1.) To sustain populations of grizzly bears and black bears under natural conditions as part of natural fauna; 2.) to minimize conflicts and unpleasant or dangerous incidents with bears through control actions; 3.) to encourage bears to lead their natural lives with minimum interference from humans. At this point, the strategy was largely criticized by Frank and John Craighead, the pioneers of grizzly bear research in Yellowstone National Park. The National Park Service was reactive rather than proactive in their management of bears, and they lacked research to achieve a basic scientific understanding of the resources they had been assigned to manage (Craighead et al. 1995). Between 1959 through 1968, there were relatively few management issues or problems with grizzly bears in the entire Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. However, after the rapid closing of all garbage dumps in the park and along its borders, human-bear interaction and conflict increased drastically (Craighead & Craighead 1971). The new management strategy was to completely phase out and eliminate open-pit garbage dumps. The abrupt change forced grizzlies into campground and areas with dense visitor occupancy leading to a drastic spike in the number of documented conflicts. "Habituated behavior demonstrated by bears is usually an indication of poor people management. Problem bears are not born, they are made (Jonkel 1993)." “We did not realize it at the time, but the close of 1967 was to be a turning point in our study. Changes in park policy would drastically affect the grizzly bear population and our research. Our population statistics, including the nine years of data on grizzly bear mortality, would now provide a basis for assessing the population changes resulting from a complete alteration in bear management policy in the park. In the years of our study prior to 1967, annual grizzly mortality, though much of it was caused by man, was still not exceeding annual gains to the population. In the six years from 1968 through 1973, 189 known deaths occurred, an average of 31.5 bears per year with maximum deaths of 53 and 48 grizzlies in 1970 and 1971, respectively. Park administrators, not knowing or not understanding the biology of bears and their low reproductive rate, would be eliminating more bears than could be annually replaced; mature females, the crucial nucleus of the population, were to be high among the casualties.” – Frank C. Craighead, Jr. Chapter 9: The Pattern of Mortality Track of the Grizzly, 1979 Insight: In 1967, the National Park Service was considering moving forward with the proposal to close down the open pit garbage/refuse dumps throughout Yellowstone National Park (commonly used by grizzly bears). The park would alternatively switch to using incineration as a means to rid of garbage created by the park and its visitors. This switch would negate potential health hazards which could result from the open refuse pits throughout the park. Closing the open pit dumps would also help assist return grizzly bears to their natural behavior, not dependent on human foods, garbage or hand-outs (Craighead 1979). The Craigheads' in general, were in favor of closing the open-pit garbage dumps. However, they were at stiff odds with the Park Service with how to achieve such a goal, without significantly impacting the current grizzly bear population (Craighead 1979). The Park Service expressed their plans to quickly close the dumps, using a "cold turkey" approach, whereas the Craigheads advised a plan that would phase out the open pit dumps over a longer time scale, with a tentative plan to monitor movements and provide supplementary food sources (Craighead 1979). The Craigheads based their reasoning on the knowledge they acquired during their research on feeding and movement patterns; these patterns that were documented could not be changed suddenly to fall in line with proposed park policy from park officials (Craighead 1979). For nearly eighty years grizzly bears in Yellowstone National Park had used garbage dumps frequently to forage for food; as park visitation increased, so did the amount of refuse being dumped in the open pits (Craighead 1979). Grizzlies repeatedly returned to these areas where they had previously found and identified a food source. The Craigheads believed that closing the dumps abruptly without providing some sort of supplementary food (elk, deer, bison carcasses) would allow bears to move into campgrounds and developed areas to forage resulting in increased incidents and human-bear conflict (Craighead 1979). Without going into grave detail, the bureaucracy involved in the events to follow was unfortunate, and can be referenced in "Chapter 10: Bureaucracy and Bear: The Grizzly Controversy, Track of the Grizzly: Frank C. Craighead, Jr. 1979." The year 1970 marked the beginning of a new management strategy for managing grizzly and black bears in Yellowstone National Park. As previously mentioned, before 1970, open dump garbage pits made human foods easily available for bears, causing what is now referred to as "food conditioning." As documented by the Craigheads, the sudden dump closures resulted in increased mortality. In six years from 1968-1973, 189 known deaths occurred, averaging 31.5 bears per year (maximum deaths of 53 and 48 grizzlies in 1970 and 1971). The newly implemented bear management strategy focused on preventing bears from obtaining any human foods, garbage or other attractants (Meagher and Phillips 1983), disregarding any suggestions made by the Craigheads regarding alternatives such as, long term phase out approaches with supplementary food sources (elk, bison, deer carcasses at the dump locations) being provided. Most of the bears that were food-conditioned found themselves at odds with park personnel and visitors and consequently were removed from the park by 1980. The number of bear mortalities during this period could have been avoided, had park managers heeded to the recommendations set forth by Frank and John Craighead. The whole ordeal, had it gone the other way, just might have changed the course of history for grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone. The decades proceeding 1980, visitation and tourism increased, and so did the populations of both grizzly and black bears. Surely, this was a sign of successful conservation strategies and protections in place (i.e. Endangered Species Act), but initially at expense of the grizzly & black bear populations. More bears were commonly found near roadsides, foraging in open meadows on native foods, close to visitors (Haroldson and Gunther 2013). The initial strategy was to prevent habituation from occurring (before 1990). At this point, roadside bears were not tolerated. Park personnel and staff were worried about the potential risk to humans (automobile accidents, conflicts, etc.). Hazing, relocation, and removal of bears by park officials were common to solve habituation issues. The beginning of the 1990s marked another subsequent change in bear management strategy: habituation tolerance. Instead of regularly and frequently hazing, relocating/trapping or removal habituated bears, the strategy of tolerating habituation was implemented. Park staff often are called to "bear jams" where bears are often in proximity to the roadway and easily observed. The main priority of park staff dispatched to bear jams is to ensure public safety. This includes ensuring vehicles are parked legally, visitors are behaving appropriately, and not creating an unsafe or unpredictable situation by approaching, harassing or feeding bears present (Richardson et al. 2015). This strategy has been in place for 29 years (1990-2019) [Meanwhile, even National Park Service personnel were quietly admitting that when it came to grizzlies, the Craighead’s had been on the right track after all. By the end of the century, shortly before Frank Craighead died in 2001, one authoritative book declared that their Society-supported grizzly bear study remained the “longest-running, most thorough, most fertile and most definitive of them all, the standard by which all subsequent study of bears has been measured.”] -Mark Jenkins National Geographic Timeline September 22, 2016 4. Bear Safety & Food Storage Grizzly bears and black bears can be found almost anywhere inside of Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Park. Odors, whether from food or other aromatic sources can attract them to come into campgrounds, developments to investigate. Food and other aromatic products which may intrigue or probe the curiosity (investigation) from a bear should be properly stored when not of immediate use. In the National Parks and some of the outlying territories, bear-resistant food storage boxes are available. When these boxes are not available, seek the use of bear canisters, or even bear sacks (can be hung and elevated). It is important that if you are camping or using the backcountry, never to store food on your person, or in your tent at night. Store all food in the proper areas, or you could receive a citation, and be fined. All of the following need to be properly stored in bear-resistant containers/boxes or your vehicle when not being actively used:

Never leave aromatic, or products containing an odor for any duration of time. All food should be easily within reach and accessible. Never allow bears to obtain a food reward; if a bear approaches you in a campground or backcountry site, never abandon your food and throw food at the bear in an attempt to distract or divert it. Throw rocks, bang pots, and pans, make noise, letting that bear know it is not welcome. At the same time, expediently clean up your area of food. Encountering a bear on a trail is much different as opposed to that in a developed area or campground setting. Backcountry areas and trails are managed so that bears have the priority. Front country and developed areas (i.e. campgrounds) are managed so that people are given the priority. If a bear is observed or encounters at close distance on the trail, slowly retreat, talk in a calm voice, do not panic. If it is possible, and you encounter a bear at distance, position yourself so you are downwind, alerting the bear to your presence as they pick up your scent (this is not always practical). Works Cited

2 Comments

1/24/2020 08:00:45 pm

I think that bears are some of the animals that we need to protect. I feel like there are some who do not view them as important, and that is just bad. I need to talk to people who actually value their existence. Bears are some of the most important animals, and they are important to the natural order of things. If you see a bear, do not poke it, do not try to even make contact with it, man.

Reply

Don Streubel

4/9/2023 03:32:44 pm

Great article, Tyler. As a long-time ago graduate of Stevens Point, your interest, knowledge and involvement in bear management in the Yellowstone Ecosystem is wonderful to see and experience. Univ. of Wisconsin, Stevens Point helped create a good number of highly educated and well trained conservationists; and you are one of them. Hope to see you this summer

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorTyler Brasington is a native born and raised Pennsylvanian, yet proud current Wisconsin resident. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater with a B.S. in Environmental Science. Currently, Tyler is pursuing his masters in Natural Resources with the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He has worked in Yellowstone National Park under the guidance and supervision of Dr. George Clokey and Dr. Jim Halfpenny. Disclaimer: The information and views expressed on this page do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Interior, US Geological Survey, National Park Service or the United States Government.

The Greater Yellowstone Grizzly Project

www.yellowstonegrizzlyproject.org © 2021 Tyler Brasington All rights reserved. No portion of this website may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, or appropriate authors, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. For permissions contact: [email protected] Archives

February 2021

Categories |

- Welcome

- Home

- About

- Submit sightings

- Family Tracker

- Publications & Research

- Natural Life History

- Cementum Age Determination for Grizzly Bears

- Nutrition & Diet

- Radio Telemetry and Wildlife Tracking

- Chemical Immobilization and Wildlife Handling

- Infectious Disease in Bears

- Effects of Wildfire on Grizzly Bears: Yellowstone 1988

- Mortality Database

- Photo gallery

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed